We have written several times on WFC’s inability to grow EPS and its ongoing regulatory problems. That said, even we were surprised that on Janet Yellen’s last day as Chair of the Federal Reserve (“Fed”), the central bank filed a consent order against Wells Fargo (“WFC”) requiring the bank take a number of extraordinary steps to improve corporate governance. While WFC does so, the Fed has taken the unusually harsh step of restricting the bank’s balance sheet growth; specifically, its total assets are not to exceed those as of 2017 year-end.

Effectively, the consent order precludes the bank from prioritizing growth until after it satisfies its regulatory requirements. The bank estimates actions taken to maintain this asset cap will reduce net income by $300 mln to $400 mln after-tax in 2018 ($0.06-$0.08 per share, or 1%-2%).

In our view, the most important takeaway is that the “invisible” tax that Wells Fargo has been paying for the past two years will have to be paid for at least another two years. This invisible tax is in the form of: (a) highly distracted management, (b) lower appetite for risk, (c) heavy board oversight, and (d) higher compliance expenses, all of which will weigh on growth in ways that are NOT easy to quantify precisely when reviewing the financial statements.

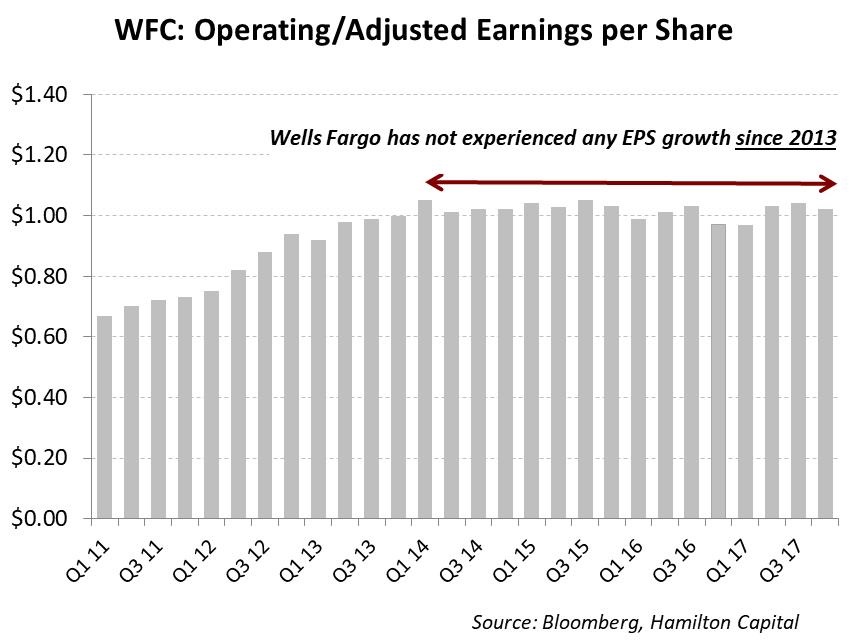

Banks need to take risk to grow and make money and the consent order will reduce WFC’s risk appetite, which will inevitably weigh on its realized growth. It is worth noting that in the past few years, WFC has continually missed analyst estimates and, in fact, has not experienced any EPS growth since 2013 (see chart below for ‘adjusted’ quarterly EPS). In 2017, the bank – again – did not meet analyst forecasts.

We have written several times about the regulatory headwinds facing WFC and tied this to its mediocre EPS growth profile. We have further argued that the bank is in the midst of a multi-year (downward) re-rating that will result in a lowering – or possibly an elimination – of its premium valuation. This year saw WFC’s premium shrink, although it did – like all U.S. firms – benefit from higher 2018 EPS estimates as a result of lower corporate tax rates.

In the next two years, we believe the overall U.S. banking sector stands to benefit from several positive catalysts including: (i) solid GDP growth, (ii) continued and gradual increases in the Fed Funds rate, and (iii) regulatory tailwinds. We also believe these catalysts favour mid-cap banks, which allow for more specific/customized geographic exposure (including to the higher growth southwest and southeast regions), have higher rate sensitivity overall and have the potential for M&A.

There are ~400 U.S. publicly traded banks in the U.S. to choose from (including ~180 mid-caps) and WFC is the only notable one forbidden from growing its balance sheet. As such, we do not believe there is a compelling case to own Wells Fargo. That said, there are many compelling reasons to own a portfolio of U.S. mid-caps banks, as mentioned above.

The Hamilton Capital U.S. Mid-Cap Financials ETF (USD) (HFMU.U) has exposure to over 40 U.S. banks, representing about two-thirds of the portfolio. The Hamilton Capital Global Bank ETF (HBG) has exposure to 25 U.S. banks for a combined weighting of ~45%. Although the Hamilton Capital Global Financials Yield ETF (HFY) has ~44% exposure to the U.S., only ~13% is to U.S. banks, owing in part to their relatively lower yields compared to global peers.